Let’s cut to the chase: Jordan Peele’s second directorial endeavor, Us, is stellar and if you haven’t seen it already you should do so immediately. I walked out of Us unable to do anything but obsess over what I had just witnessed. If I could’ve, I would’ve walked right back to the ticket counter and gone for a second round.

Spoilers ahoy! Proceed with caution.

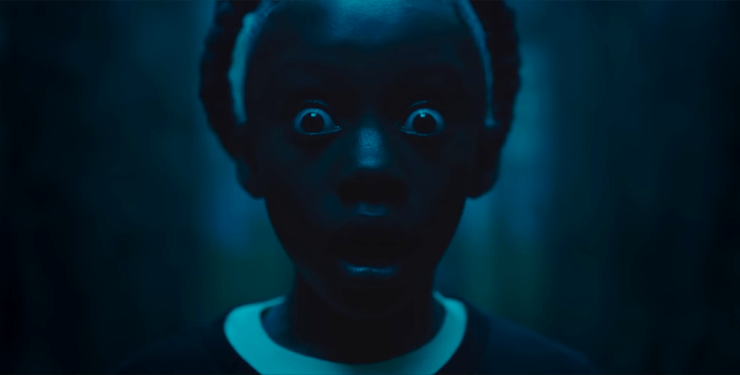

It all starts with a family vacation. Young Adelaide (Madison Curry) tags along behind her quarreling parents during a 1986 trip to the Santa Cruz Beach Boardwalk. We see the world from her height and perspective—her parents little more than angry, faceless figures always at a distance. They stand miles apart, their child the weak tether keeping them together. That lack of connection sends Adelaide off on her own, down to the stormy shore and into a creepy hall of mirrors where she comes face to face with a nightmare version of herself.

Three decades later, Adelaide (Lupita Nyong’o) is back at Santa Cruz, this time with her hunky dork of a husband Gabe (Winston Duke) and their two children Zora (Shahadi Wright Joseph) and Jason (Evan Alex). Adelaide’s adult family is the polar opposite of her childhood one. Theirs is a foundation built on love and empathy, albeit sometimes lacking in understanding. Still, a sense of dread looms over the humor of a dad with his junky boat, bickering siblings, and an offbeat hip-hop sing-along. This isn’t a fun getaway for Adelaide; not with all the traumatic memories it dredges up.

That night, the world ends as the Shadows emerge from the tunnels. We don’t know that, not at first. Peele structures the arrival of the Shadow Wilsons as a direct and personal assault that gradually expands until it consumes everyone and everything. What starts out as a suburban family under attack becomes the zombie apocalypse, an evolution that few directors could pull off. Peele doesn’t so much sprinkle clues as he does put up a giant billboard advertising them, but like any good horror film you don’t really know what you’re looking at until it’s too late. In spite of the occasional stumbles—the big reveal of how the Shadows came to be makes things more confusing, not less—Us is a goddamn masterpiece.

Through his astonishing work in Get Out and now Us, Jordan Peele has more than proven himself to be a genius of the horror genre. He manipulates tropes and expands what the genre is capable of in ways both subtle and obvious by making calculated, deeply clever choices. Every single thing on camera, from dialogue to facial expressions to clothing to mise-en-scène means something, even if it’s not obvious on the first, second, fifth, or tenth viewing.

What is Us really about? Everything. The film demands that its audience theorize and speculate. It’s about poverty or slavery or immigration or imperialism or classism or capitalism or white guilt or gentrification or the consequences of the American dream. It’s an homage to Hitchcock or Romero or Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining, a reference to Sisters or C.H.U.D. or A Nightmare on Elm Street or Jaws or Michael Jackson’s Thriller. According to Peele himself, Us is a Rorschach test. It is whatever we say it is and more than we realize.

At its most fundamental level, the film uses horror tropes to fuck with the primal drive that pits “us” versus “them.” This group is right, that one is wrong. These people are good, those are bad. I deserve everything, you are entitled to nothing. We justify our violence against others by calling them brutes, mindless monsters, invaders.

Buy the Book

The Survival of Molly Southborne

Adelaide and Red are both an “us” and a “them” simultaneously. Red uses the skills she retained from her life above ground to help the Shadow people revolt against their masters, while Adelaide becomes more and more Shadow-like as her battle with Red intensifies. Red cannot shake her aboveground influences anymore than Adelaide can ignore her underground instincts. When Red reminds Adelaide that Adelaide didn’t have to imprison Red in the tunnels, that she could’ve taken her with her, the two women further blur the lines between “us” and “them.”

In truth, there is no “us” and “them.” Only “we.” And if we are all the same, then what do we owe to those we once shunned and exploited? Does changing the funhouse’s name from the painfully stereotypical “Shaman’s Vision Quest” to the bland “Merlin’s Enchanted Forest” while keeping the interior exactly the same make up for the damage caused by the old name? Was the 1986 Hands Across America anti-poverty campaign still a success if less than half of the $34 million that was raised by generating a temporary sense of good will, unity, and sentimentality made it to the people who desperately needed it? Us insists that hiding our crimes does not negate them. Beneath our shiny new masks lies the cold, hard, bloody truth.

It’s not just about exploring divisions between the oppressed and the oppressors, but the justification of that oppression. Us is about dealing with our culpability. It doesn’t matter that the Wilsons didn’t know what was happening to their clones; they are still responsible for the system that allowed the clones to exist in the first place.

Peele demonstrates this in numerous ways, but one of the most intriguing and effective methods is through language. Red speaks English, but the rest can only grunt and howl. Except there’s nothing “only” about these noises—when Abe calls out to another Shadow on the other side of the lake, it becomes clear that those sounds are really part of their language. They can communicate—we just can’t understand them. Our instincts are to assume that they are thoughtless, emotionless beasts, and the Shadows are clever enough to use those assumptions as weapons against their counterparts. By the end, we realize the Shadows have a culture, a community, a language, and a belief system. They don’t just look like us, they are us. They aren’t monsters…they’re people.

And while Us isn’t strictly about race, it works best with a Black family as its center. As author and professor Tananarive Due notes, Us isn’t just a horror movie, it’s a Black horror movie. Gabe’s Howard sweater, their car, their nice vacation home, the new but shabby boat, all put them solidly in the upwardly mobile middle class. When comparing them to the Tylers, there’s an undercurrent of commentary on the lack of generational wealth in Black families and white privilege based around home ownership and net worth. Look at how Gabe code-switches his tone when he’s trying to get the Shadow Wilsons to leave his driveway from overly polite requests to AAVE threats. Even the music takes on new meaning. Peele has the Wilsons play Luniz’ 1995 hit “I Got 5 On It” while the Tylers get “Good Vibrations” by the Beach Boys: two feel-good party songs for drastically different communities. Later the Tylers play “Fuck tha Police” by NWA, a song often adopted and gentrified by white fans who want to dabble in Black culture without understanding the systemic oppression that inspired the lyrics (while also embracing the opportunity to say the N-word without repercussion).

In terms of the look of the film, the way cinematographer Mike Gioulakis shoots Black skin is nothing short of astounding. Gioulakis finds texture in using darkness and shadows as a way to obscure or highlight the cast. He treats dark skin not like a bug that has to be forced to fit the current system, but as a feature that the system can be manipulated to enhance.

If all the technical brilliance, theory, and filmmaking nuance hasn’t convinced you of Us’ glory, Lupita Nyong’o’s mindblowing performance should. Everyone in Us is phenomenal (hats off to Curry and Joseph, especially) but Nyong’o’s acting broke me. Might as well just hold the Oscars now, because no one will put in a performance stronger than Lupita Nyong’o. And she does it twice! She’s been great in roles before, but after Us it’s obvious that Hollywood has been wasting her prodigious talents. I want her cast in everything, immediately.

Us may not be as allegorical or as clearly social justice-oriented as Get Out, but that doesn’t make it a lesser film, in any way. With Easter eggs crammed into every frame, Us demands multiple viewings. It’s a deeply weird, wonky, intentionally confounding and inexplicable movie that will haunt me for years to come, and I look forward to seeing it again and again.

Alex Brown is a high school librarian by day, local historian by night, author and writer by passion, and an ace/aro Black woman all the time. Keep up with her on Twitter and Insta, or follow along with her reading adventures on her blog.